A virus is genetic material contained within an organic particle that invades living cells and uses their host's metabolic processes to produce a new generation of viral particles.

The way they do this varies. Some insert their genetic material into the host's DNA, where it can sit in wait until it's translated at a later date. As the host cell replicates itself, it can make new viruses.

Viruses can also burst their host cell as they expand in numbers, in what's called a lytic cycle of reproduction.

How big are viruses?

The word virus comes from a Latin word describing poisonous liquids. This is because early forms of isolating and imaging microbes couldn't capture such tiny particles.

Virus sizes vary from the extremely minuscule - 17 nanometre wide Porcine Circovirus, for example - to monsters that challenge the very definition of 'virus', such as the 2.3 micrometre Tupanvirus.

Similarly, they come in a range of complexities, containing different proteins or surrounded by an array of shells and envelopes to assist in their infection and reproduction of just about every species across every kingdom of life.

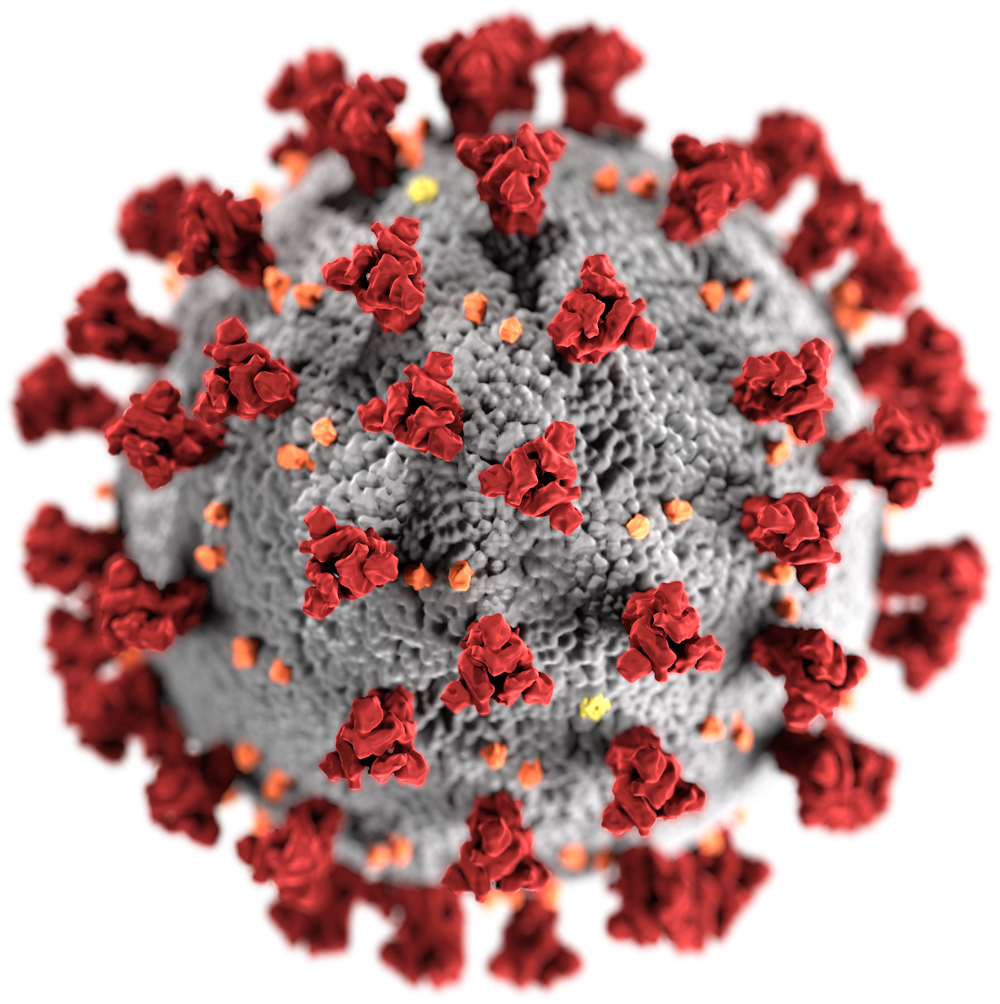

Viruses can be encoded in a variety of ways. Rotaviruses are based on a double strand of RNA, for example. Coronaviruses have a single strand of RNA, which is 'positive sense', as in it can be translated directly into new proteins. Influenza has negative sense RNA, meaning it needs an extra transcribing step before it can make proteins.

Smallpox and herpes viruses are examples of DNA viruses, which force the host to transcribe its genome into RNA on entry.

Sizes of these genomes also vary. Some of the largest can be over a million base pairs long. On the other hand, an RNA virus that infects bacteria, called MS2, has barely 3,500 base pairs.

It's impossible to know with certainty just how many types of viruses exist in the natural world, with numbers climbing as researchers use new tools to search for classified and unknown genetic signatures in the soil, oceans, and even the skies. Rough estimates suggest there could be as many as 100 million types of virus on Earth's surface.

Are viruses alive?

This is a question scientists continue to discuss as definitions of life and ecology change. Current thinking suggests viruses should be considered part of a complex living system, one that extends between all organisms.

'Virions' are the inactive particles that move through the environment, which we don't tend to think of as alive. Only once they're part of a cell do viruses take on living characteristics of their own, borrowing the host's biochemistry to reproduce.

As such, it's more accurate to think of viruses as part of the continuum between chemistry and biology, one that isn't clearly divided

什么是病毒

https://cutt.ly/ltTIqNe

病毒是一种包含在有机颗粒中的遗传物质,该颗粒会侵入活细胞并利用其宿主的代谢过程产生新一代病毒颗粒。

他们执行此操作的方式各不相同。有些人将他们的遗传物质插入宿主的DNA中,可以放置在那里,直到以后翻译。随着宿主细胞自我复制,它可以制造新病毒。

病毒还可以随着其数量的膨胀而破裂其宿主细胞,这就是所谓的繁殖裂解周期。

病毒有多大?

病毒一词来自拉丁语,描述有毒液体。这是因为分离和成像微生物的早期形式无法捕获如此微小的颗粒。

病毒的大小从极小的微粒(例如17纳米宽的猪圆环病毒)到挑战“病毒”定义的怪物,例如2.3微米的Tupanvirus。into living and non-living.

同样,它们具有一系列复杂性,包含不同的蛋白质,或者被一系列的壳和包膜包围,以帮助它们感染和繁殖每个生命王国中的几乎每个物种。

病毒可以通过多种方式进行编码。轮状病毒例如基于RNA的双链。冠状病毒具有单链RNA,具有“正向意义”,因为它可以直接翻译成新蛋白质。流感具有负义RNA,这意味着它需要额外的转录步骤才能制造蛋白质。

天花和疱疹病毒就是DNA病毒的例子,它们迫使宿主在进入时将其基因组转录成RNA。

这些基因组的大小也不同。最大的一些可能超过一百万个碱基对。另一方面,一种感染细菌的RNA病毒,称为MS2,仅有3500个碱基对。

无法确定自然世界中存在多少种病毒,随着研究人员使用新工具在土壤,海洋甚至天空中寻找机密和未知的遗传特征,数字正在攀升。粗略估计表明,地球表面上可能有多达1亿种病毒。

病毒还活着吗?

随着生命和生态变化的定义,这是科学家继续讨论的问题。当前的想法表明,应将病毒视为复杂的生命系统的一部分,该系统在所有生物之间传播。

“病毒粒子”是在环境中移动的惰性粒子,我们通常不认为它们是活的。病毒一旦进入细胞,它们便会发挥自身的生存特征,借用宿主的生物化学进行繁殖。

因此,将病毒视为化学和生物学之间连续体的一部分是更准确的,这没有明确划分